Feb 01, 2024

Stories of Care and Courage: Virginia Allen and the Black Angels

The Campaign for Action is pleased to recognize Black History Month with this powerful story about Black nurses recruited in the late 1920s to care for patients with active tuberculosis (TB), a painful and debilitating contagious disease that killed 5.6 million U.S. residents between 1900 and 1950.

The year was 1947, and the invitation to leave her childhood home in Detroit came from an admired aunt who worked as a nurse in New York City. Few teenagers pack up, leave their families, and head to a distant city to take a dangerous job, but Virginia Allen did just that. Though only 16 years old, Allen set out on a journey that would involve her in one of the 20th century’s major medical breakthroughs.

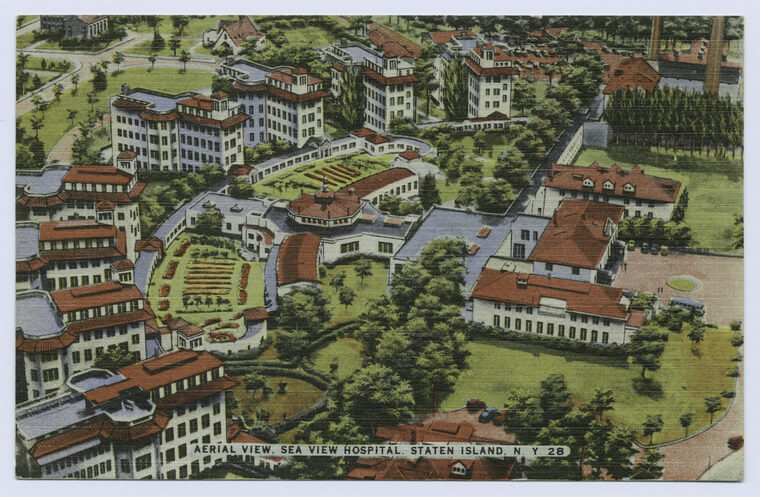

Allen is one of the last living Black Angels—a name patients gave the Black nurses recruited to staff Staten Island’s Sea View Hospital at the end of the 1920s. They cared for patients with active tuberculosis (TB), a painful and debilitating contagious disease that killed 5.6 million U.S. residents between 1900 and 1950. In New York City alone, the disease killed 10,000 people annually before the city opened a sanatorium on Staten Island, where, in those days, TB patients would find sunlight, fresh air, and plenty of rest—the standard treatment for the disease at the time.

In the seven years following Sea View’s opening in 1913, TB deaths fell by almost 50%. Isolating patients, who typically lived in crowded tenements, was effective in reducing the spread of the disease, but TB itself remained without a cure. Caring for TB patients was hazardous and stigmatizing work, and in the 1920s, the white nurses who initially staffed Sea View began fleeing the facility for safer employment.

Black Nurses Answer the Call

As the nursing shortage became increasingly dire toward the end of the decade, Sea View actively began to recruit Black nurses. The hospital offered room, board, and on-the-job training leading to licensure in addition to a small salary. Allen’s aunt, Edna Sutton, was one of the first to answer the call. Like dozens of others, she decided to leave her family and the Jim Crow south to pursue one of the few professional opportunities open to her. Hospitals were largely segregated in the 1920s, and those that served Black patients lacked the financial resources to hire staff nurses. Instead, they relied on student trainees, inadvertently producing a cadre of Black nurses with few places to put their skills to work. As of 1933, an estimated 250 of Sea View’s 300 nurses were Black.

When New York’s hospitals faced a new nursing shortage in 1947, the city’s Black nurses saw an opportunity to raise the economic prospects of family and friends. They went to work filling hospital vacancies, and soon Allen had joined the Sea View staff as a nurse’s aide. She was assigned to the children’s building and went on to receive training to become a licensed practical nurse (LPN).

“To be perfectly frank, I had no fear, and I didn’t realize how deadly tuberculosis was,” Allen recalled during a recent telephone call. Unlike some of the Black Angels who came before her, she has fond memories of her years at Sea View. “The working conditions were pleasant, and I enjoyed working with children. I found it a challenge, not a chore,” she says. “I was learning every day.”

This positive outlook sustained Allen in the face of some daunting challenges. She cared for children with pus-filled blisters, painful rashes, and the heartache of family separation. They screamed and cried and threw tantrums. She was especially moved by the plight of the toddlers and spent long hours holding them and reading to them.

Full recovery from TB was still rare when Allen arrived at Sea View in 1947, but the prognosis for patients was starting to improve. The hospital had begun using experimental drugs that allowed some adults to recover. Children were not part of the drug trials, but Allen says just being at Sea View was curative. Compared to the crowded tenements most patients normally inhabited, the hospital was a much healthier environment. “The children seemed to thrive with the fresh air, very rich diet, and plenty of rest,” she recalls.

Recovered History

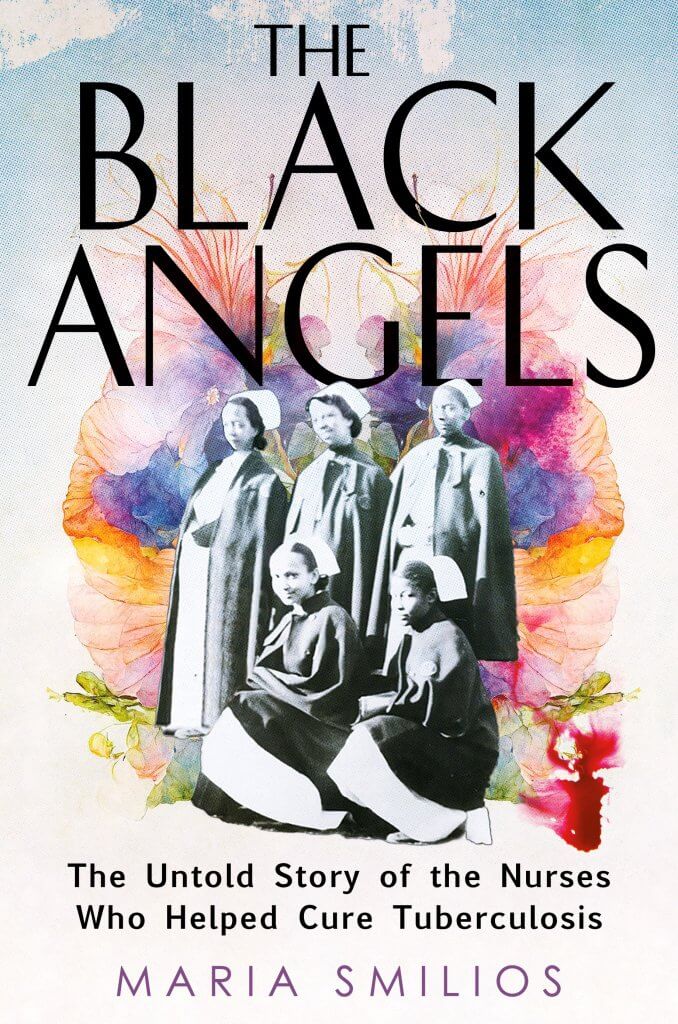

This history is now seeing the light of day thanks to Allen and others, including Maria Smilios, who describes it in detail in her 2023 book, The Black Angels. In addition to telling their story, the book vividly describes the indignities Black nurses faced, not only in the south but also at Sea View and other hospitals in New York City. As late as the 1930s, segregated dining was the norm, white supervisors were abusive, and Black nurses were reprimanded and sometimes demoted for speaking up. With only four of the city’s 26 municipal hospitals hiring Black nurses, they held onto their jobs despite the working conditions, applying pressure where they could improve them.

In 1908, Black nurses, who were banned from the American Nurses Association (ANA), formed their own professional organization, the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (NACGN). They aimed to raise professional standards, develop leadership, and fight the discrimination they faced. According to Smilios, “They inspired all of these Black nurses across the country to reach for the Black press,” which informed city officials about discriminatory hiring practices and unequal treatment of patients inside hospitals.

At Harlem Hospital, for instance, women in the Black maternity wards were dying in childbirth at twice the rate of those in the white wards, Smilios reports. Her book also tells the story of one politically savvy nurse who leveraged the mayor’s need for Black votes during an election year to successfully petition city hall to integrate Harlem Hospital’s lunchroom. “That was reversed later on in retaliation,” Smilios says, but despite setbacks, progress inched forward. In 1944, the leader of the NACGN met with Eleanor Roosevelt and successfully lobbied the U.S. military to do away with quotas on the hiring of Black nurses. By 1951, major progress had been achieved. The number of state nursing associations prohibiting Black nurse membership had declined from 17 to five, the number of nursing schools admitting qualified Black candidates had grown from 28 to 330, and the once all-white ANA had opened its doors to all comers.

A Medical Breakthrough

With its 1,800-strong patient population, Sea View offered a ready testing ground for potential TB cures. Its patients were diverse in terms of age, gender, and degree of illness, and the hospital had physicians who fully understood the disease and knew how to run clinical trials. Administering the medications and documenting their effects fell to Sea View’s Black Angels.

In the summer of 1951, Sea View began testing a new antibiotic—isoniazid—on the hospital’s sickest patients. In a matter of weeks, their health was largely restored without the side effects or rebounds produced by some earlier drugs. The trials were expanded, doses were adjusted, and isoniazid was tested in combination with other drugs. The work of Sea View’s physicians and nurses led to a historic breakthrough—the discovery of a cocktail of treatments that were 95% effective in ensuring recovery from TB.

Children were not part of the original isoniazid trials, but Allen had a front-row seat as these developments unfolded. “It was such a joy to see so many patients discharged to go home and take the medication from home and be treated in that way,” she told the Staten Island Museum, which is also working to preserve and share her story.

Epilogue

In 1957, Allen left Sea View to work for Local 1199, now part of the Service Employees International Union, and later returned to hospital work as an operating room nurse and administrator. She remains active today as a volunteer with Lambda Kappa Mu Sorority, the National Council of Negro Women, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and the Staten Island Ballet. While TB continues to be a leading infectious killer globally, large sanitariums are no longer needed to treat the relatively small number of U.S. cases. Today Sea View provides high quality short-term rehabilitation and long-term skilled nursing care, and its former dormitories have been converted into senior housing. Today Virginia Allen is one of the residents, living just down the hall from the room she inhabited 76 years ago.

To learn more

The Staten Island Museum’s online exhibition, Apart Together, features audio recordings of Virginia Allen’s recollections. The museum will open an on-site exhibit, Taking Care, on January 26, 2024.

Fauteux is founder and principal at Propensity, LLC, a communications firm serving educational institutions and nonprofits focused on health care, health policy, and the health professions.

McCamey is founder, CEO and president of DNPs of Color, Inc. and assistant dean of Strategic Partnerships at Johns Hopkins University School of Nursing.

Caption 1: Irma and Paul Milstein Division of United States History, Local History and Genealogy, The New York Public Library. “Aerial View Sea View Hospital, Staten Island N.Y. 28” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47d9-cb86-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

Caption 2: Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Photographs and Prints Division, The New York Public Library. “Army nurses standing at attention in front of their barracks and being inspected by staff officers, Army nurse training center, England” New York Public Library Digital Collections. Accessed January 25, 2024. https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47df-fa17-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99